Refusal to Employ

Employers are required to walk a tight-rope every time they hire a new employee.

The Fair Work Provisions that prohibit discrimination against prospective employees are broad. However, in reality, these situations are almost impossible to enforce.

Discrimination is an essential aspect of the human condition. We ‘discriminate’ thousands of times a day. When we choose the foods we are going to eat, the people we spend our time with, and, at which exact moment to cross the road. Having the capacity and confidence to discriminate between our life options is what keeps us safe, and makes us successful humans.

When making employment decisions, however, including recruitment decisions, those characteristics that represent ‘lawful’ discrimination and ‘unlawful’ discrimination are not always easy to navigate. Requiring an employee to have ’30 years’ experience’ is not the same as requiring that person to be ‘over 45’, but there is an essential nexus between these two states that is hard to ignore in practical terms. On the other hand, there is nothing unlawful about choosing a candidate on the basis of lack of experience, on the grounds that they will potentially cost less, especially in the event that a Modern Award provides that someone below the age of 20 can be paid a lower minimum rate. Yet, refusing to hire someone because they are not ‘young’ is clearly unlawful.

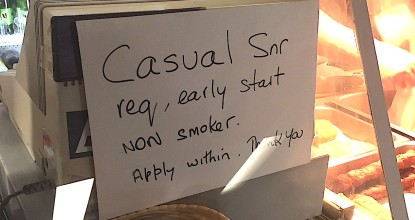

Employers who actively advertise for ‘Junior’ or ‘Senior’ employees flirt dangerously with this subtle distinction.

The Fair Work Act provides broad protections against this type of unlawful decision, by prohibiting adverse action against prospective employees on unlawful discriminatory grounds. Under section 342, adverse action against a prospective employee includes ‘refusing to employ’ that employee, and under section 351 this adverse action cannot be taken for reasons that include “race, colour, sex, sexual orientation, age, physical or mental disability, marital status, family or carer’s responsibilities, pregnancy, religion, political opinion, national extraction or social origin.”

The unlawful reason needs to be only one of the reasons, and once an allegation is made, the employer would bear the onus of ‘proving otherwise’.

Most of these protections are obvious ‘no brainers’. They protect us from discrimination on the grounds of the key personal characteristics that we all should know are plainly and obviously wrong. They are supported by concurrent state and commonwealth antidiscrimination legislation, which are based on international law. Section 351, however, goes a little bit further than the domestic and international antidiscrimination standard, and the full scope of the provision is not easy to pin down, especially when we look critically at some of the more ‘marginal’ characteristics. This is especially the case when the reverse onus is taken into account. For example, would it be unlawful for the ACTU to ‘refuse to employ’ a candidate because they discover, in a pre-interview social media screen, that the candidate ‘likes’ Cory Bernardi on Facebook – clearly a ‘political opinion’?

Is it ok for an interviewer to ask a candidate ‘What are your responsibilities outside of work? Are you able to take on overtime shifts at short notice?’ and then base part of the decision on this answer? Or could this be regarded in some circumstances as a refusal to employ based on ‘family or carer’s responsibilities’. Put more broadly, does it become unlawful to factor ‘availability’ into this decision. Clearly, this is a relevant employment consideration, yet also dangerously discriminatory in certain circumstances. Would an employer, seeking an employee with high level logical ability, discriminate against a prospective employee on the basis of what that employer considered to be an illogical religious belief expressed during an interview?

In many cases, disaggregating ‘lawful’ from ‘unlawful’ considerations is actually a lot more difficult than most of us are comfortable admitting to ourselves.

Perhaps my favourite example is my hypothetical law school grads, Bobby and Robbie. They are the final two candidates competing for a position in a traditional top tier firm. Their resumes, academic transcripts, and experience are virtually identical. Bobby was a high school rugby union star from Knox Grammar. Robbie was a high school rugby league star from St Gregory’s Campbelltown. The defining moment in Bobby’s successful interview with the Senior Partner was the conversation on the way out the door, when the Senior Partner asks Bobbie his thoughts on the Wallabies’ chances in the next world cup. As an employment litigator and rugby league fanatic, I would take some pleasure in cross examining the Senior Partner in the Federal Court, where he would be required by the Fair Work Act to discharge a positive onus to prove that ‘social origin’ was not a substantial and operative factor that actuated his decision to favour Bobby over Robbie.

But perhaps what is most appealing about this hypothetical (aside from the fact that it has brought the topic of rugby league to a conversation where it is not typically invited) is that it illustrates the key practical reality of this issue. This court case would never happen, because these decisions are made privately and confidentially, and many of these prejudices are buried deeply. The High Court have recently held that ‘unconsious’ decisions cannot offend the general protections provisions. It is not possible to positively prove something that you don’t consciously know. The sad truth is that the most deeply held biases are held on this level.

Pre-employment discrimination protections exist in a broad and comprehensive manner in Australia, but they are almost impossible to rely upon. Even with the reverse onus in play, these forms of discrimination are almost impossible to prove, even if you have a knowledge or reasonable suspicion that it has occurred.

The mind of the pre-employment discriminator is a closed book, and they have been playing this game for along time.