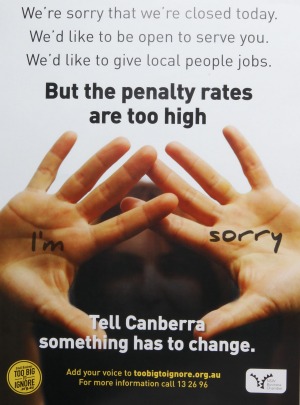

The penalty rate argument has been steadily brewing since the Coalition took office 18 months ago, spurred on by the recent decision of Restaurant and Catering Association of Victoria [2014] FWCFB 1996 which I discussed in this post. It’s not surprising that the penalty rates argument would come up over the Easter Weekend where NSW and Victoria both have gazetted four public holidays in succession. As with so many aspects of workplace law, the public conversation has been fueled heavily with emotion and political speculation, leaving the real issues stretched to opposite extremes. But the debate reached fever pitch after a very poorly conceived advertising campaign by the ACCI. Peter Martin, Jenna Price, and Heath Aston have all published opinion pieces in recent days in the Sydney Morning Herald expressing the community’s distaste.

Before entering the debate I should express my gratitude for being one of the many Australians that didn’t have to work over the Easter weekend. (Although of course being self employed, making the choice not to work also meant that I didn’t earn any money). I should also express gratitude for the many people that did work to make my long weekend enjoyable – making cappuccinos, working in shopping centres, risking life and limb to referee football games, and driving the ambulances that I thankfully didn’t happen to need. Thank you to all and Happy Easter.

But I also feel the need to assert that the debate is being blown out of hand. The ACCI can lobby Canberra as much as they wish on this, but it will make little difference other than to antagonize the community. This is because the current Coalition government are simply unable to make this wide-scale change to workplace law (including changes to the currency or content of the Modern Award system) without convincing the senate, which appears to be strongly against almost all of their attempted social and financial reforms. If the current media and polls are to be believed, the Coalition’s popularity is suffering, and at this stage just managing a lower house majority at the next election will require an ambitious turnaround, let alone achieving control of the senate. But even if they did somehow pull off an electoral miracle in 2016, memories are fairly fresh of the political fate which met the last Howard Government’s attempt to capitalise on a senate majority with radical workplace legislation. In real terms, the political debate over penalty rates is more in the field of business vs community rhetoric than any prospect of real legislative change.

The reality is that without major changes to the Fair Work Act, the Fair Work Commission will retain control over the modern awards. Their decision in the Restaurant and Catering case in relation to the Modern Restaurant Award demonstrates only very small signs of a careful attitudinal shift – and only in recognition of the limited modern social difference between Saturdays and Sundays. There has been no suggestion that they are ready to jettison penalty rates altogether. The Commission accepted that for senior employees, the Sunday penalty represented a significant segment of their weekly income, and only reduced the Sunday penalty rate for Introductory level and Grade 1 employees in the Modern Restaurant Award from 150% to 125% (to be the same as the current Saturday penalty). Employees classified as Grade 2 and above still receive the Sunday rate. In layman’s terms, this has meant that only employees whose duties are restricted to clearing tables, washing dishes, cleaning, or who are inexperienced trainees, are effected by the change – and this change is only a 20% overall reduction for one day. For anyone who serves a customer, makes a drink, coffee, or prepares any food the status quo has been retained (the vast majority of staff in the restaurant industry are either Grade 2 and above, or rapidly on their way to becoming Grade 2 or above). This reflects the Fair Work Commission’s assessment that those employed on a significant basis within the industry should not be subject to a reduction in income. For the minority concerned this is a relevant change, but hardly a social revolution.

The socio-economic and political discourse this issue inspires is always heated. (Martin’s intelligent points on class and ‘co-ordinated leisure’ are particularly engaging). But to boil this issue down into a polarized debate between human rights and economic progress misses one of the key issues – the incentive value that penalty rates hold for workers. Penalty rates do not exist just to compensate the worker for their social losses, they partly serve to act as an incentive to get people to work the shifts the rest of society requires. Conservative free market politicians might wave unemployment figures around as if this incentive is no longer necessary, but ask any restaurant owner or hospital manager how difficult it is to staff their workplaces on weekends in the current environment, let alone if penalty rates are jettisoned. There is no coincidence that the professions that currently face mass skills and qualification shortages (such as chefs and nurses) are also the ones that are expected to ply their trade 24/7. This is yet another area of industry in which the casualisation of our workforce has back-fired. If the price is not right, sought after workers can simply say no.

While I always enjoy a bit of public hysteria about workplace law – I don’t think the ACCI should be counting their chickens on penalty rate reform any day soon.

* Helen Carter is the Director and founding solicitor at PCC Lawyers, a team of employment practitioners based in Sydney, with many years of combined knowledge and experience in workplace law, industrial relations, workplace investigations and training. They provide a high standard of excellence and an exceptional level of personal service to a variety of clients in the Sydney metropolitan area, Central Coast, regional NSW and interstate.