Dismissals ‘R’ Us: A New Trend in ‘shake down’ litigation putting commercial pressure on Employers

Following some emerging trends in representative conduct in the Unfair Dismissal jurisdiction in particular, the Fair Work Commission require broader powers to make costs orders, especially against lawyers and paid agents who bring, or continue, claims that lack merit.

The Fair Work Commission’s power to make orders for costs under the Act are limited, primarily to situations in which an ‘unreasonable act or omission’ in the conduct of the matter causes costs to be incurred by the other party. The threshold of ‘unreasonableness’ is high. The traditional rationale is, that in a situation of power or resource imbalance, parties should not be deterred from litigation by the threat of costs orders. This is an essential feature of the ‘fair go all round’. There would be limited utility in providing vulnerable employees with protection under or 3-2 of the Act, if access to litigation was inhibited by the same power imbalance that protection is designed to address.

However, the traditional disparity between parties has arguably shifted. Access to free, or contingency based, representation, from unions, lawyers, or non-lawyer paid agents, is available to applicants to a level that it not available to respondents. And the involvement of these applicant representatives often mean that employers are uncomfortable proceeding without their own representation. Efforts that have been made to simplify and lower the cost of termination disputes, for the benefit of unrepresented parties, have encouraged the involvement of representatives acting outside the purview of the Legal Services Commissioner, and at times these representatives lack a thorough understanding of the provisions. In unfair dismissal applications, a push towards alternative dispute resolution has created an expectation on respondents that they should provide settlement options early in every single case, irrespective of merit. Given the cost of legal representation for respondents, and the relatively limited compensatory level of each claim, it is rarely commercially sound to resist a claim past conciliation, even if the claim fundamentally lacks merit. The high threshold of ‘unreasonableness’ in the costs provisions, has the effect of insulating applicants and paid agents from any consequences relating to the institution or continuation of unmeritorious claims. Applications can be used to leverage a result commercially, with little regard for the actual provisions. A divergence now exists between law in action, and law in principle.

However, the traditional disparity between parties has arguably shifted. Access to free, or contingency based, representation, from unions, lawyers, or non-lawyer paid agents, is available to applicants to a level that it not available to respondents. And the involvement of these applicant representatives often mean that employers are uncomfortable proceeding without their own representation. Efforts that have been made to simplify and lower the cost of termination disputes, for the benefit of unrepresented parties, have encouraged the involvement of representatives acting outside the purview of the Legal Services Commissioner, and at times these representatives lack a thorough understanding of the provisions. In unfair dismissal applications, a push towards alternative dispute resolution has created an expectation on respondents that they should provide settlement options early in every single case, irrespective of merit. Given the cost of legal representation for respondents, and the relatively limited compensatory level of each claim, it is rarely commercially sound to resist a claim past conciliation, even if the claim fundamentally lacks merit. The high threshold of ‘unreasonableness’ in the costs provisions, has the effect of insulating applicants and paid agents from any consequences relating to the institution or continuation of unmeritorious claims. Applications can be used to leverage a result commercially, with little regard for the actual provisions. A divergence now exists between law in action, and law in principle.

Meanwhile, Unions are also excluded from section 401 of the Fair Work Act, because they are not required to have permission to appear. Costs orders cannot be made against them when they act as representatives for their members. This allows Union representatives a considerable litigious freedom, with limited responsibility. For many years Unions have benefited from the receipt of civil penalties awarded against employers by the Federal Circuit Court and Federal Court. Unions therefore, have enjoyed a unique position in which they hold an incentive to bring claims on behalf of their members, yet no disincentive against vexatious and unreasonable conduct.

Meanwhile, Unions are also excluded from section 401 of the Fair Work Act, because they are not required to have permission to appear. Costs orders cannot be made against them when they act as representatives for their members. This allows Union representatives a considerable litigious freedom, with limited responsibility. For many years Unions have benefited from the receipt of civil penalties awarded against employers by the Federal Circuit Court and Federal Court. Unions therefore, have enjoyed a unique position in which they hold an incentive to bring claims on behalf of their members, yet no disincentive against vexatious and unreasonable conduct.

This applicant power, and the divergence between legal reality and legal principle, flows back to the workplace. The legislative provision that currently dictates whether a dismissal is ‘harsh, unjust, or unreasonable’ is section 387 of the Fair Work Act. This is purposed as both a general deterrent to employers, as well as practical guide to the dismissal process. However, employers are experiencing increasing levels of ‘shake down’ litigation, and are very aware of these commercial factors. This has created a disincentive to regard the section 387 guidelines in practice. As employers become more and more accustomed to having to settle claims, there is little point in performing dismissals fairly in the first place. In this respect, the Act is failing to achieve its purpose.

There is no easy solution, but very slight changes in the costs jurisdiction may have the effect of addressing this emerging imbalance. These changes should focus on regulating the conduct of representatives. Unrepresented applicants should remain largely insulated from costs orders. However, a broader scope for costs orders against all representatives would be desirable to further the purposes of the Act. These can be effected by three steps. Firstly, added procedural obligations in the Fair Work Commission Rules, for representatives in relation to both the bringing, and resisting, of claims. These may include representatives providing undertakings on the original application and response that the claim is brought or resisted with reasonable prospects of success. Further, instructions on a contingency or pro bono basis should be disclosed to the Commission, and parties making that disclosure should be compelled to apply to the Commission for permission to cease representation. Fair Work Commission Conciliators and parties should be given broad power to apply to the Commission for intervention in the event that either the procedural obligations are breached, or if it appears that a claim has been brought without merit.

There is no easy solution, but very slight changes in the costs jurisdiction may have the effect of addressing this emerging imbalance. These changes should focus on regulating the conduct of representatives. Unrepresented applicants should remain largely insulated from costs orders. However, a broader scope for costs orders against all representatives would be desirable to further the purposes of the Act. These can be effected by three steps. Firstly, added procedural obligations in the Fair Work Commission Rules, for representatives in relation to both the bringing, and resisting, of claims. These may include representatives providing undertakings on the original application and response that the claim is brought or resisted with reasonable prospects of success. Further, instructions on a contingency or pro bono basis should be disclosed to the Commission, and parties making that disclosure should be compelled to apply to the Commission for permission to cease representation. Fair Work Commission Conciliators and parties should be given broad power to apply to the Commission for intervention in the event that either the procedural obligations are breached, or if it appears that a claim has been brought without merit.

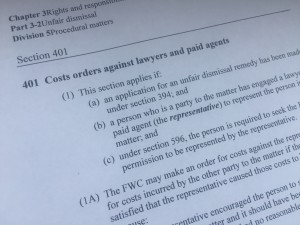

Secondly, the phrase ‘unreasonable act or omission’, in section 401 of the Act, should be defined to further include any breach of the new procedural obligations for representatives. This would broaden the powers of the Commission to make costs orders in specific circumstances, and encourage greater respect for the legal provisions from many paid agents and lawyers.

Thirdly, Unions should no longer be protected from costs orders by the Act. Like all other agents in this space, they should be held responsibilities for any unreasonable conduct.

This content is general in nature and provides a summary of the issues covered. It is not intended to be, nor should it be relied upon, as legal or professional advice for specific employment situations.